The Quiyoughcohannocks (key-yock-co-hannocks) were one of the first native groups the English encountered when they sailed up the James in May 1607. The Quiyoughcohannocks, whose principal weroance village was situated upriver from Mount Pleasant near Claremont in Surry County, would also prove to be among the settlers’ best allies, until the pressures of English settlement eventually overwhelmed them. While visiting the Paspaheghs, whose village was near the confluence of the James and Chickahominy rivers, the Jamestown colonists were visited by the Quiyoughcohannock weroance Pepsicuminah (often referred to mistakenly by the English as “Rapahanna”). George Percy recorded their first memorable encounter:

The next day, being the fifth of May, the weroance of Rapahanna sent a messenger to have us come to him. We entertained the said messenger and gave him trifles, which pleased him. We manned our shallop with muskets and targeteers sufficiently; this said messenger guided us where our determination was to go.

When we landed, the weroance of Rapahanna came down to the waterside with all his train, as goodly men as any I have seen of savages or Christians. The weroance, coming before them playing on a flute made of a reed, with a crown of deer’s hair colored red in fashion of a rose fastened about his knot of hair, and a great plate of copper on the other side of his head, with two long feathers in fashion of a pair of horns placed in the midst of his crown, his body was painted all with crimson, with a chain of beads about his neck, his face painted blue, besprinkled with silver ore as we thought, his ears all behung with bracelets of pearl, and in either ear, a bird’s claw through it beset with fine copper or gold; he entertained us in so modest a proud fashion as though he had been a prince of civil government, holding his countenance without laughter or any such ill behavior. He caused his mat to be spread on the ground, where he sat down with great majesty, taking a pipe of tobacco, the rest of his company standing about him.

After he had rested awhile, he rose and made signs to us to come to his town; he went foremost, and all the rest of his people and ourselves followed him up a steep hill where his palace was settled. We passed through the woods in fine paths, having most pleasant springs which issued from the mountains. We also went through the goodliest corn fields that ever was seen in any country. When we came to Rapahanno’s town, he entertained us in good humanity.

During the early years of the Jamestown settlement, Pepsicuminah maintained good relations with the newcomers while other native groups proved less hospitable. As John Smith himself remarked, the weroance of the Quiyoughcohannocks was an “honest, proper, good, promise-keeping king,” who “did always at our greatest need supply us with victuals of all sorts, which he did notwithstanding the continual wars which we had in the rest of his country, and upon his deathbed charged his people that they should forever keep good quiet with the English”.

In the wake of the great Native American Uprising of 1622 (see ahead), the English launched punitive expeditions against the Quiyoughcohannocks and those other groups that had participated in the attacks. Though they burned their villages and seized their crops, the English were not immediately successful in displacing the Native Americans from their traditional Southside territory. But ultimately the flood of English settlers into the James River valley proved overwhelming to the native peoples, whose numbers were dwindling in the face of sporadic fighting and European disease, and by the 1630s, the Quiyoughcohannocks were gone.

Although the main Quiyoughcohannock village was located nearly 10 miles away, much Late Woodland pottery has been found in the fields around Mount Pleasant. The main concentration of pottery, however, occurs in the yard on the north side of the main house where archaeological investigation of the landscape also has uncovered posthole patterns of sections of Native American long houses. Preliminary analysis of the Native American pottery from Mount Pleasant indicates that Quiyoughcohannock ceramics have a distinctive combination of clay fabric and decoration that is strikingly similar to Native American pottery that has been recovered from the recent excavations at James Fort. This suggests an exciting avenue of potential research on the level of unrecorded interactions, such as trading for food, between the Quiyoughcohannocks and the English during the early years of Jamestown.

In 1618 the Virginia Company of London received its third and final charter from King James I. Soon after, Company officials issued instructions to Governor George Yeardley, which brought about certain sweeping changes that ultimately assured the success of the Virginia colony. Foremost was the introduction of a system that made private land ownership legally possible. The new land policy (known as the headright system) provided an incentive to prospective immigrants to leave overcrowded England and seek their fortunes in Virginia. This in turn helped alleviate the colony’s labor shortage, for men and women who could not afford to pay for their own transportation to the colony immigrate as indentured servants. Moreover, once they had completed their term of indenture, they could become landowners themselves. The prospect of acquiring massive tracts of land also encouraged groups of wealthy investors to underwrite part of the expense of colonization. In combination, these factors fueled the spread of settlement and attracted new immigrants and investors to the colony.

One early colonist who took advantage of the new Virginia Company policies was Richard Pace, who came to Virginia with his wife Isabell sometime before 1616. Initially, the Paces, who as “ancient planters” in Virginia prior to 1616 and thus eligible for a dividend of 100 acres per person, were granted 200 acres of land along the southside of the James River. Although the Paces Paines plantation lasted little more than a decade before it was subsumed into the larger Swann’s Point plantation, Richard Pace and Chanco, a Native American servant living at Paces Paines, had an everlasting effect on the course of American history for their roles in the Uprising of 1622.

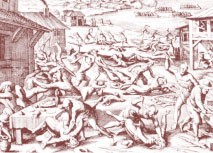

By 1622, the English had taken over the land of all the tribes along the James River. The inevitable reaction to the relentless English encroachment on Native lands was the well-known uprising of 1622. On the morning of March 22, 1622, the Powhatans under the leadership of Opechancanough, who became the paramount chief upon the death of his brother Powhatan in 1618, attacked English settlements along both sides of the James River. Nearly one-quarter of the English population in Virginia was killed by the coordinated raids. However, when Chanco learned of the plans the uprising, he told Richard Pace. Pace then immediately informed Jamestown of the plot, which was thus prepared to defend itself. The following is a contemporary account of the events:

The slaughter had been universall, if God had not put into the heart of an Indian belonging to one Perry, to disclose it, who liuing in the house of one Pace, was urged by another Indian his Brother (who came the night before to lay with him) to kill Pace, (so commanded by their King as he declared) as hee would kill Perry: telling further that by such an houre in the morning a number would come from diuers places to finish the Execution, who failed not at the time: Perries Indian rose out of his bed and reueals it to Pace, that vsed him as a Sonne: And thus the rest of the Colony that had warning giuen them, by this meanes was saued,

Pace vpon this discouery, securing his house, before day rowed ouer the Riuer to James City (in that place neere three miles in bredth) and gaaue notice thereof to the Gouernor, by which meanes they were preuented there, and at such other Plantations as possible for a timely intelligence to be giuen.

A 1625 muster of the Virginia colony indicates that here were four separate households at Paces Paines. The archaeological survey of Mount Pleasant has discovered one of the four Paces Paines’ sites in the downriver or east field. The artifacts collected from the site are the same types that have been excavated at Martin’s Hundred including clay tobacco pipe bowls (one with markings identical to a pipe from Wolstenholme Town), fragments of Rhenish stoneware Bartmann or “bearded man” jugs, Iberian costrel sherds, and pieces of Staffordshire butterpot.

In 1635, William Swann patented 1200 acres that included the Paces Paines tract. Thomas Swann I inherited the plantation in 1638, which then descended in 1680 to Samuel Swann. Thomas and Samuel both had their homes across “Mount Swamp” on the eastern half of the property along Gray’s Creek. The seventeenth-century Swann house site, which has been archaeologically tested, is not far from the Swann family cemetery.

The south field at Mount Pleasant contains a large archaeological site that apparently originated sometime in the late seventeenth century during the Swann era. The only test excavation in the site revealed a twelve-foot wide chimney base for a frame building. The chimney base has a significant northeast-southwest orientation, unlike the true north-south orientation of the present dwelling at Mount Pleasant. It is conceivable that this site marks the dwelling that stood prior to the construction of Mount Pleasant, and perhaps the home of John Hartwell.

In 1709, John Hartwell acquired the 1650 acre Swann’s Point plantation that included Mount Pleasant. The tract eventually fell to Richard Cocke IV around 1730 when he married Hartwell’s daughter and heir, Elizabeth. About 1750 they built the present dwelling and later it was named Mount Pleasant.

There are no surviving plats, maps, drawings, or insurance policies to indicate the location of any eighteenth-century structures at Mount Pleasant. However, archaeological testing and ground-penetrating radar have discovered a cluster of outbuildings that extend north to south just off the east wing. The northernmost outbuilding closest to the wing, Structure I, measures about 18‘ by 27‘ and may be as long as forty-five feet. Adjacent to the foundation of this structure is a five-foot deep cellar that is either an addition or a separate, perhaps earlier, building. The cellar fill contains a wealth of artifacts and seems to have been filled around 1800.

About forty feet east of this building is a second cellar, Structure II. Although the cellar has been tested, the rest of the structure has not been located. This cellar also was filled in the late eighteenth century, and produced several intriguing artifacts including two cowrie shells and glass beads. Cowrie shells, which come from either the Indian Ocean or the Caribbean, are associated with enslaved Africans.

A third eighteenth-century dependency is located immediately south of Structure I where testing uncovered several foundations, both continuous footings and brick piers, that represent either a single large eighteenth-century structure or possibly two separate buildings.

Artifacts from the site in the south field suggest that it continued to be used through the eighteenth century as well. Also, there is a probable slave quarter site in the northwest corner of the west field.

The archaeological testing and ground-penetrating radar survey both indicate that there are no corresponding structures on the west side of the house just as there is no archaeological evidence that there ever was a west wing at Mount Pleasant.